What does it mean to be an American?

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in Sacramento, Calif., where four talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people from various walks of life—whether they are Indigenous, native born, a naturalized citizen, a refugee or an immigrant without legal status—to ask what it means to be an American.

Abi Mustapha is a biracial artist and activist who paints portraits of people who look like her in her studio in Santa Cruz, CA. Malakai Wade reports on what it means for Mustapha to push back against what she’s been taught Americans should look like.

Illustration by Emily Whang

How a biracial artist grew to appreciate her American identity through art and activism

Abi Mustapha paints people who look like her — curly hair, dark skin, rich colors and joyful faces. For her, drawing portraits of other biracial people make up for the lack of representation she saw growing up.

“The more I paint people who look like me and see other people appreciating it, the more I appreciate myself,” she said.

Art as dissent against the 'American' narrative

Abi Mustapha takes a moment to pose in front of one of the largest paintings in her studio on Tuesday, Oct. 12, 2021. She describes her art as “flowery and goddessy,” painting big hair and big smiles. (Photo by Malakai Wade)

Mustapha grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in a primarily white community. Her father is from Sierra Leone and her mother is a white American. At home, her father cooked a lot of West African food and she often spent time around other people of color, but at school she still didn’t feel like she fit in.

“It wasn’t the same experience that my peers were having, for sure. As an adult, I really appreciate that,” she said. “As a kid, I didn’t. I wanted my name to be Jennifer Smith instead of Abi Mustapha.”

She regularly has to remind herself that she has just as much right as anybody else to be seen and exist in any space, she said.

“Sometimes when I’m at the beach and I’m like, ‘oh, there aren’t many people that look like me.’ I’m like, ‘yeah, and you’re just allowed to be here,’” she said. “That’s shifted a lot. It’s a lot of undoing and unlearning.”

The life of an artist and activist wasn’t something Mustapha had originally planned for herself.

Abi Mustapha works on the details of a painting in her Santa Cruz, Calif. studio on Tuesday, Oct. 12, 2021. (Photo by Malakai Wade)

At Indiana University, she studied political science and sustainability and then found herself working in horticulture.

It wasn’t until after she moved to Oakland eight years ago that she met a lot of artists who showed her that she could flourish in an artistic career. She also participated in peaceful dissent and creative protest with the Black Lives Matter and Women’s March movements.

“That, to me, seems the most American. That seems the most patriotic,” she said.

Mustapha’s paintings are purposefully flowery and colorful and depict a range of ages and skin tones. She likes to emulate Art Nouveau, a turn-of-the-century style that typically focuses on women in delicate, feminine poses with lots of flowers and plants. She said her paintings contrast the historical style to showcase more representation.

Abi Mustapha works on a large painting in her studio in Santa Cruz, Calif. on Tuesday, Oct. 12, 2021. Mustapha uses oil paint to get the rich colors in her works, and loves incorporating flowers and leaves in her portraits. (Photo by Malakai Wade)

At Indiana University, she studied political science and sustainability and then found herself working in horticulture.

It wasn’t until after she moved to Oakland eight years ago that she met a lot of artists who showed her that she could flourish in an artistic career. She also participated in peaceful dissent and creative protest with the Black Lives Matter and Women’s March movements.

“That, to me, seems the most American. That seems the most patriotic,” she said.

Mustapha’s paintings are purposefully flowery and colorful and depict a range of ages and skin tones. She likes to emulate Art Nouveau, a turn-of-the-century style that typically focuses on women in delicate, feminine poses with lots of flowers and plants. She said her paintings contrast the historical style to showcase more representation.

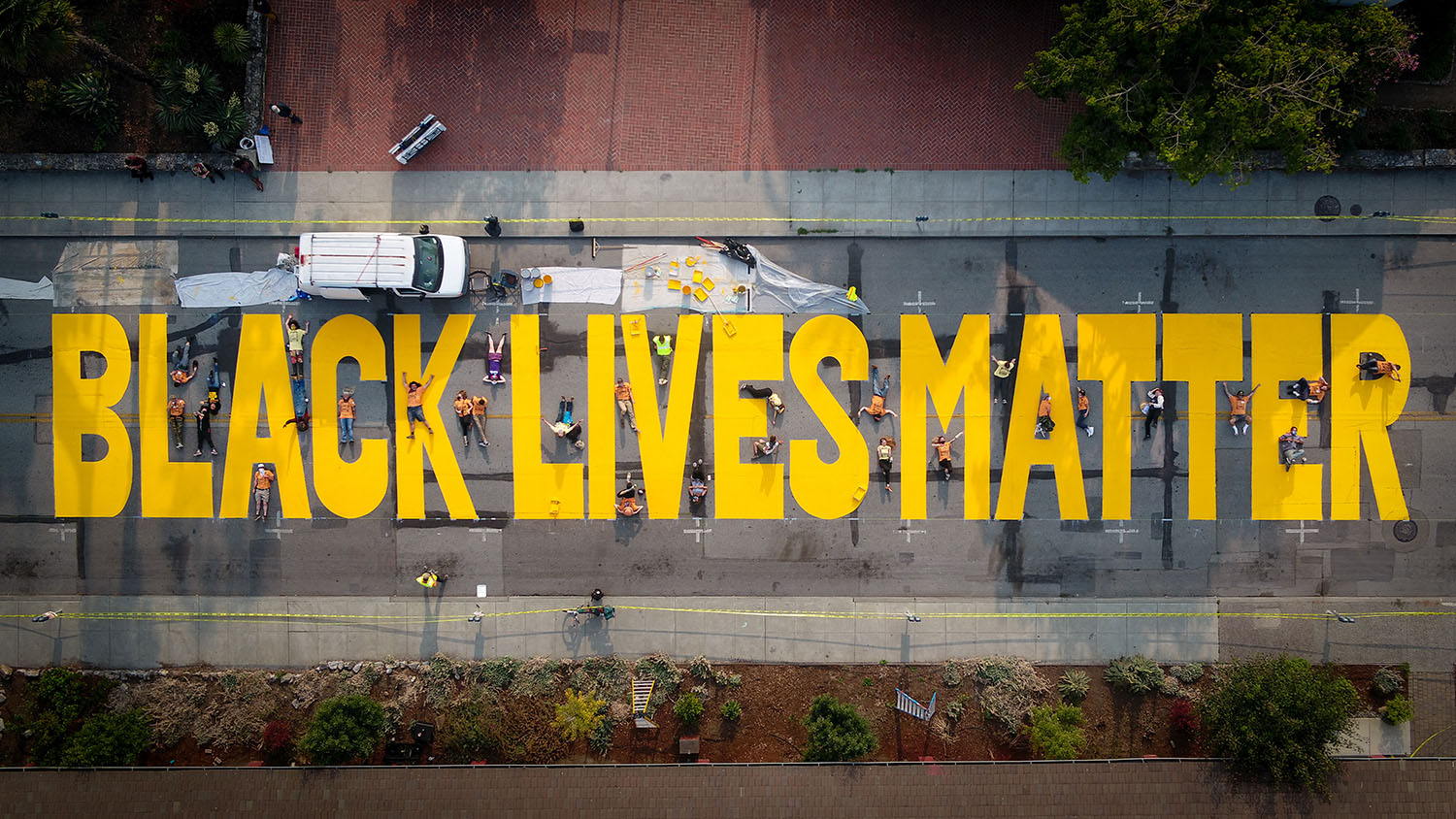

Volunteers pose with the Black Lives Matter mural after it was painted on Saturday, Sept. 12, 2020. (Photo Courtesy of Swan Dive Media)

Mustapha was also at the forefront of creating the Black Lives Matter street mural in downtown Santa Cruz, inspired by a similar mural in Oakland. Unsure of the temperature of race relations in Santa Cruz, she decided to look into the permit process.

Painted in September 2020, the mural has been host to several events, and Mustapha explained that the process to create the mural ignited the possibility of racial equity and change in Santa Cruz County. Since the mural would shine a spotlight on the city, she wanted to make sure that Santa Cruz had some measurable and equitable change planned.

“If this is going to give our city racial equity clout, then the city needs to give us some actual racial equity,” she said.

After Mutapha and a group of volunteers completed the mural in front of City Hall in September 2020, it was soon defaced. Less than a year later, two young, white men posted a video of themselves driving black tire marks across the large yellow letters, burning the rubber in a snaking pattern down the street.

They were arrested, and their trial began on Oct. 7th. Mustapha and other local activists have been fighting for restorative justice, hoping that the two men would work with and for the community to paint over the tire marks.

Before the permit expires in 10 years, Mustapha wants to pass on the stewardship of the mural to others. She hopes that the mural — like her own art — continues to bring awareness to systemic racism in America and further inspires a paradigm shift in equality.

“We might not need this mural anymore, and it [the movement] could morph into something else.” she said.