What does it mean to be an American?

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nprnextgenradio project is created in Sacramento, Calif., where four talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are speaking to people from various walks of life—whether they are Indigenous, native born, a naturalized citizen, a refugee or an immigrant without legal status—to ask what it means to be an American.

Sunnie Ishtimonabi, a Black and Chickasaw College student living in Oakland, is navigating what it means to be American and a Black Native. She shares the sometimes lonely experience of not feeling wholly seen by either her Black or Native communities, but finds the beauty in being a descendant of rich traditions and culture.

Illustration by Ard Su

Am I a ghost? A Black and Indigenous college student embodies dual identity

During a windy evening on Indigenous People’s Day, one of the most important holidays for Native people, Sunnie Ishtimonabi (she/her, they/them) sat in her college’s library to think about where she fits and how she should feel about this holiday as a Black Chickasaw person.

“There are times when I literally think I come from ghosts and I’m like am I here?” Sunnie asks. “And so you do kind of question, am I valid? Am I real?”

Sunnie Ishtimonabi smiles while on her campus at Mills College in Oakland, California. (Photo by Carolann Jane Duro)

As a descendant from the Chickasaw nation, Sunnie is from one of the so-called five civilized tribes that enslaved Black people in an attempt to assimilate into the colonizing elite class in America. Although Sunnie is well acquainted with her own family history, many Americans aren’t aware that the Chickasaw nation enslaved 975 people, roughly 18 percent of their population. Sunnie’s own history is made up of a Chickasaw great great great grandfather who married a runaway enslaved Black woman.

Sunnie is firmly rooted in her ancestry despite other people’s lack of knowledge of this American history.

“I think if someone were to ask the question like, ‘Are you American?’ And I’d say, no, and I would just say, I’m Homs’losa or I’m a Black Chickasaw.”

Sunnie is part of a growing trend of people in the United States identifying as multiracial.

Over a quarter of adults with a white, Black, and American Indian biracial background identify as multicultural, according to a study conducted by Pew Research. But while Sunnie embraces their multicultural identity, she doesn’t feel American.

“I think being American means to take things from people who have been displaced or from people who have been here forever. And to take that for yourself,” they said.

Sunnie holds a picture of her Black Chickasaw Great Great Grandmother, the matriarch of her homa’losa heritage, along with her husband. (Photo by Carolann Jane Duro)

Sunnie is talking about settler colonialism, a type of colonialism that functions to replace Indigenous populations with an invasive settler society that over time develops a distinct identity.

She doesn’t always feel like she belongs in the spaces she wants to claim. Sunnie often feels out of place within the Indigenous community because they physically present as Black.

Sunnie finds herself trying to signal her Native identity with her clothes and accessories.

“I never leave the house without beaded earrings because I feel like if I don’t wear them like no one’s going to be able to tell [that they are Indigenous],” Sunnie said.

Sunnie wears braided sage green earrings to signify her Native identity. Sunnie practices beading earrings in her free time. (Photo by Carolann Jane Duro)

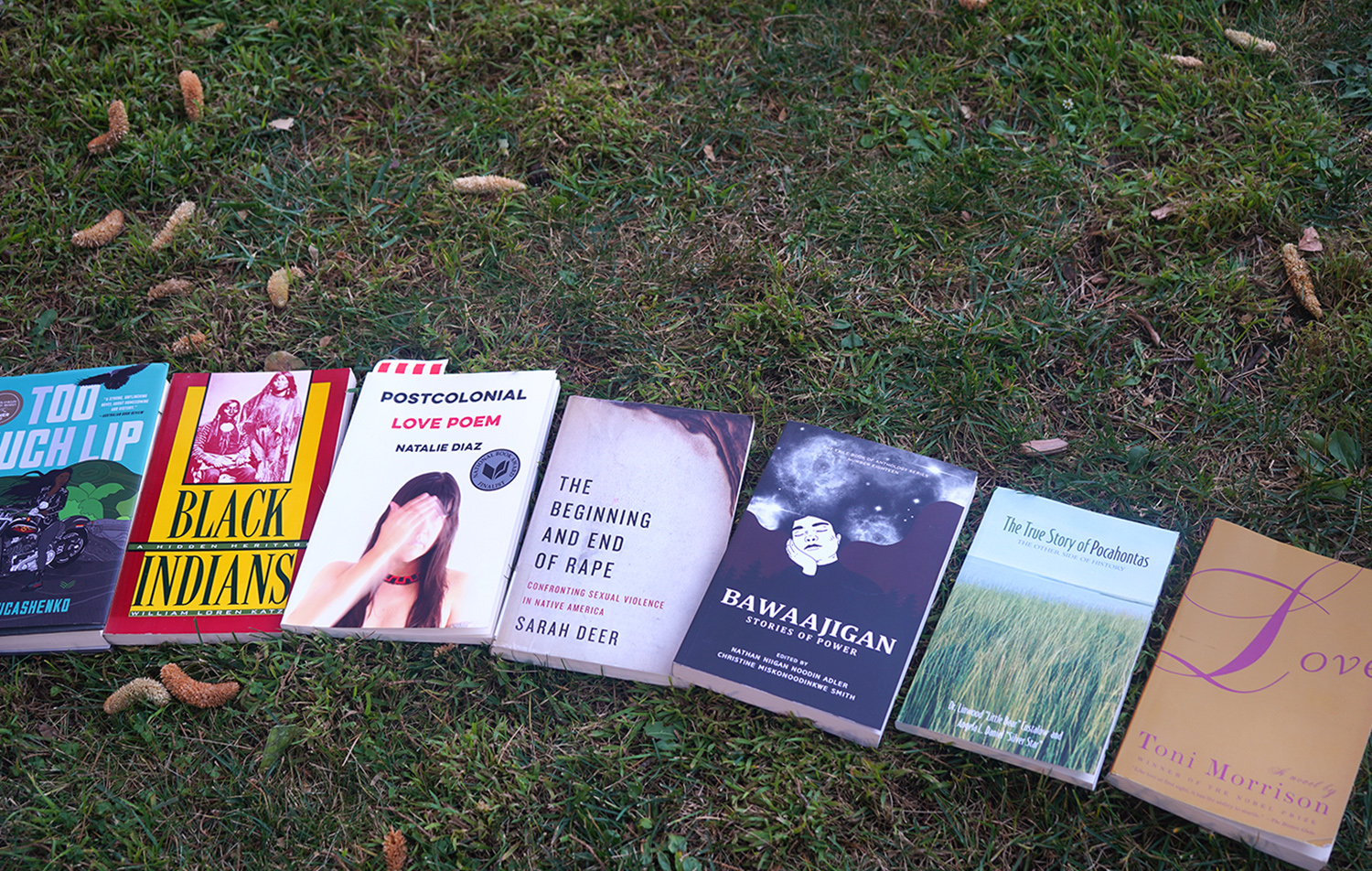

An array of books lay on the lawn, one of Sunnie’s favorite spots on campus. All of these books are by Indigenous authors or about Indigenous peoples. (Photo by Carolann Jane Duro)

Since the history of Black-Indigenous identity is not commonly taught in this country, many Black and Indigenous people are caught in a web of misconceptions and mythologies. Sunnie finds that in the Indigenous community, some Indigenous people believe you can’t be Indigenous if you are Black. And in the Black community, some believe that you can only be Black and not Indigenous.

“Within Indian Country have kind of tried to get me to pick a side. I can’t rip myself in half. That’s not how that works,” Sunnie said.

Sunnie is always looking for spaces that acknowledge her dual identities. She’s found that books and stories help her come alive and feel seen. She says her favorite book is Too Much Lip by Melissa Lucashenko, a novel about a Black and Aboriginal Australian queer woman.

“When I read that book, I hold that book so close to my heart, it means everything to me. Because just the story, the things that the character went through is very much my story and has very much validated me and let me know that it’s OK,” Sunnie said.

More and more people are becoming familiar with these complex histories. Social media accounts like the Choctaw and Chickasaw Freedmen Twitter aim to fight for rights of Black Freedmen and shine a light on Black Native experiences. As more of these stories become known, experiences like Sunnie’s are finding their way into the forefront.

Sunnie awakens when she joyfully expresses the hope she finds in Black and Indigenous histories of resistance, “I love the shared history of being Black and Native, not just of like the shared history of mixing, but the shared history of people in the five tribes who have helped enslaved people escape to freedom.”

Sunnie stands in the middle of the photo with her Auntie Cousin, her Ishkosi’ (as mentioned in the audio piece) to the right, Sunnie’s dad to the left, and her Ishkosi’s daughter to the furthest right. Sunnie says that her Ishkosi’ invented the word Homs’losa to mean Red/Black. (Photo courtesy of Sunnie Ishtimonabi)